Posttraumatische stressstoornis (PTSS) is een aanzienlijk probleem voor de volksgezondheid waarvoor bestaande therapieën slechts marginaal effectief zijn. Onbetwistbaar is de primaire behandelingslijn voor PTSS psychotherapie, volgens de huidige behandelrichtlijnen. Desondanks blijft PTSS een chronische aandoening, zelfs na psychotherapie, met hoge percentages psychiatrische en medische aandoeningen. Er is een dringende behoefte om nieuwe verbindingen en benaderingen te zoeken voor het beheer van PTSS. Het gebruik van LSD is een nieuwe methode. Dit artikel bekijkt de doeltreffendheid van LSD bij de behandeling van PTSS en het verbeteren van de resultaten voor patiënten. Het omvat ook een overzicht van de therapeutische rechtvaardiging, het gebruikskader en het beschikbare bewijsniveau voor LSD. Er worden verschillende vragen geformuleerd die in toekomstig onderzoek kunnen worden bestudeerd om een beter begrip van het onderwerp te krijgen.

Trefwoorden: Posttraumatische Stressstoornis, PTSS, LSD

Inleiding en achtergrond

Posttraumatische stressstoornis (PTSS) is een complexe psychische stoornis die jaarlijks 7,7 miljoen volwassenen in de Verenigde Staten treft, waarbij één op de 11 individuen op enig moment in hun leven de diagnose PTSS krijgt. Meer dan twee keer zoveel vrouwen (10%) als mannen (4%) hebben PTSS, waarbij seksueel misbruik de meest voorkomende traumatische gebeurtenis is [1]. Volgens de criteria van de DSM-5 is PTSS een psychische stoornis die kan ontstaan na blootstelling aan een traumatische gebeurtenis, zoals dood, ernstig letsel of seksueel geweld [2]. PTSS wordt gekenmerkt door terugkerende en verontrustende symptomen die minstens één maand na de traumatische gebeurtenis aanhouden. Symptomen van PTSS omvatten dissociatieve reacties, verontrustende dromen, vermijding van trauma-gerelateerde stimuli, voortdurende psychologische stress, ongunstige veranderingen in cognitie en stemming, en variatie in opwinding en reactievermogen [3].

De selectieve serotonineheropnameremmers (SSRI's) sertraline en paroxetine zijn door de Amerikaanse Food and Drug Administration (FDA) goedgekeurde eerstelijnsbehandelingen voor PTSS [2]. Naar schatting 40-60% van de patiënten die met deze verbindingen worden behandeld, ondervindt geen enkele reactie [4]. Hoewel op trauma gerichte psychotherapieën, zoals langdurige blootstelling en cognitieve gedragstherapie, worden beschouwd als de meest effectieve behandelingen voor PTSS, reageren veel mensen niet goed op deze behandelingen of blijven ze significante symptomen hebben, en de uitvalpercentages zijn hoog [4]. Slechte behandelingsresultaten worden vaak geassocieerd met bijkomende aandoeningen zoals kindertijdstrauma, alcohol- en drugsgebruik, depressie en dissociatie [2]. Daarom is het essentieel om een gunstige behandeling te identificeren voor degenen die doorgaans resistent zijn tegen behandeling.

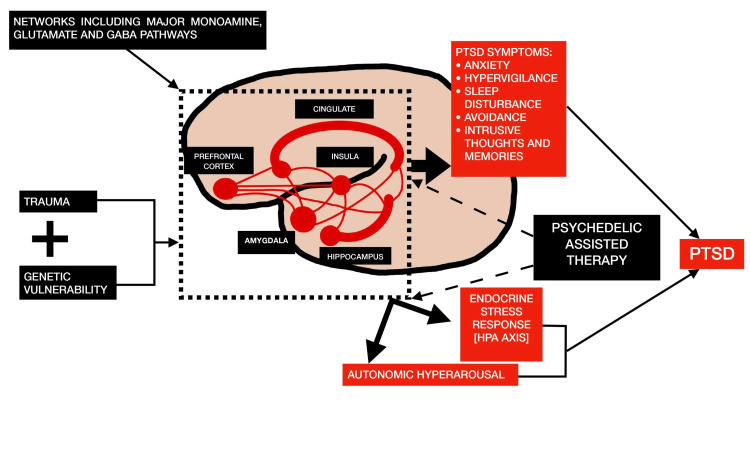

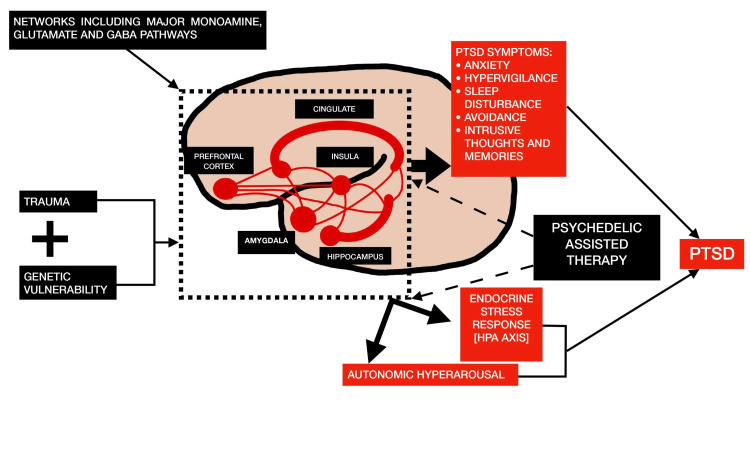

De neurale netwerken (cingulate, insulaire, prefrontale cortex, amygdala en hippocampus) die betrokken zijn bij de monoamine-neurotransmitters zoals serotonine, dopamine en glutamaat, worden gewijzigd in PTSS als gevolg van trauma. De endocriene en autonome zenuwstelsels worden vervolgens beïnvloed door deze netwerkveranderingen, wat leidt tot de fysiologische en subjectieve symptomen van PTSS. Het neurale netwerk en de subjectieve niveaus van dit proces is waar LSD de meest waarneembare effecten heeft [7].

Fig. illustreert het veronderstelde effect van psychedelische-ondersteunde therapie op de pathofysiologie van PTSS [7].

Figuur 1 Het veronderstelde effect van LSD op de pathofysiologie van PTSS omvat de reacties van het hypothalamus-hypofyse-bijnier (HPA)-systeem.

Er is hernieuwde interesse in LSD als geneesmiddel binnen de geneesmiddelenontwikkeling. Er is hernieuwde belangstelling voor de therapeutische voordelen voor aandoeningen variërend van depressie en middelenmisbruik tot PTSS [4].

Dit traditionele reviewartikel zal de doeltreffendheid van LSD bespreken bij de behandeling van PTSS en het verbeteren van de resultaten voor patiënten. Het zal het huidige onderzoek over het onderwerp verkennen en de voor- en nadelen van LSD beoordelen. Denk bijvoorbeeld aan het feit dat LSD het vermogen heeft om hogere bewustzijnstoestanden op te wekken.

Zie hier het bewijs dat momenteel beschikbaar is voor LSD, evenals achtergrondinformatie over de therapeutische rechtvaardiging, de context waarin het wordt gebruikt, en het huidige niveau van bewijs dat beschikbaar is voor de behandeling van PTSS.

Zoekstrategie

We hebben uitgebreid gezocht in de databases van PubMed, Google Scholar en ScienceDirect voor Engelstalige literatuur. Uitgebreid onderzoek werd uitgevoerd met trefwoorden om de studies te valideren die de doeltreffendheid van LSD bij de behandeling van PTSS analyseert en beoordeelt. Trefwoorden omvatten lyserginezuurdi-ethylamide (LSD), MDMA, ketamine, psilocybine, PTSS, psychedelische-ondersteunde therapie, hallucinogenen, cannabinoïden, dimethyltryptamine (DMT) en synaptische connectiviteit. Alle artikelen werden overwogen zonder beperkingen qua publicatietijd of onderzoekstype, zoals traditionele reviews, systematische reviews, klinische onderzoeken, case-control studies en cohortstudies. Studies werden niet verfijnd op basis van leeftijd en etniciteit, en de zoekopdracht had geen demografische beperkingen. Dierstudies werden uitgesloten. Omdat dit een traditioneel reviewartikel is, zijn de richtlijnen van de Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) niet gevolgd. Gegevens werden verzameld vanaf het begin tot oktober 2022.

Review

Lyserginezuurdi-ethylamide (LSD) is een geneesmiddel dat werkt voornamelijk door agonistische activiteit op de 5-HT2A-receptor [4]. Sommige patiënten kunnen emotionele kwetsbaarheid vertonen in de dagen na het gebruik [43]. LSD kan een verhoogde hartslag en bloeddruk veroorzaken. Daarom zijn sommige vormen van hypertensie en ernstige cardiovasculaire pathologieën contra-indicaties. LSD is niet schadelijk voor het menselijk lichaam en leidt niet tot afhankelijkheid of significante bijwerkingen (zoals flashbacks) [45].

Conclusies

PTSS blijft vaak een chronische aandoening met hoge percentages van psychologische en medische comorbiditeit. Nieuwe therapieën die de effectiviteit van PTSS-behandelingen kunnen verbeteren, zijn daarom dringend nodig. Zoals deze review benadrukt, biedt LSD perspectief voor een revolutionaire methode om PTSS te behandelen. LSD heeft een uniek potentieel, van hun gebruik om snel PTSS-symptomen aan te pakken tot hun gebruik als aanvullingen ter ondersteuning van psychotherapie.

References

1.

The efficacy of MDMA (3,4-Methylenedioxymethamphetamine) for post-traumatic stress disorder in humans: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Tedesco S, Gajaram G, Chida S, et al. Cureus. 2021;13:0. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]3.

Post-traumatic stress disorder. Shalev A, Liberzon I, Marmar C. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:2459–2469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]4.

Reviewing the potential of psychedelics for the treatment of PTSD. Krediet E, Bostoen T, Breeksema J, van Schagen A, Passie T, Vermetten E. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2020;23:385–400. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]5.

Psychedelics and psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. Reiff CM, Richman EE, Nemeroff CB, et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177:391–410. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]6.

Investigational drugs for assisting psychotherapy for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): emerging approaches and shifting paradigms in the era of psychedelic medicine. Averill LA, Abdallah CG. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2022;31:133–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]7.

Review of potential psychedelic treatments for PTSD. Henner RL, Keshavan MS, Hill KP. J Neurol Sci. 2022;439:120302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]8.

The early use of MDMA (‘Ecstasy’) in psychotherapy (1977-1985) Passie T. Drug Science. 2018;4:1–19. [Google Scholar]9.

The safety and efficacy of {+/-}3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine-assisted psychotherapy in subjects with chronic, treatment-resistant posttraumatic stress disorder: the first randomized controlled pilot study. Mithoefer MC, Wagner MT, Mithoefer AT, Jerome L, Doblin R. J Psychopharmacol. 2011;25:439–452. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]10.

First study of safety and tolerability of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)-assisted psychotherapy in patients with alcohol use disorder: preliminary data on the first four participants. Sessa B, Sakal C, O'Brien S, Nutt D. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12:0. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]11.

Reduction in social anxiety after MDMA-assisted psychotherapy with autistic adults: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled pilot study. Danforth AL, Grob CS, Struble C, et al. Psychopharmacology. 2018;235:3137–3148. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]12.

MDMA-assisted psychotherapy for treatment of PTSD: study design and rationale for phase 3 trials based on pooled analysis of six phase 2 randomized controlled trials. Mithoefer MC, Feduccia AA, Jerome L, et al. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2019;236:2735–2745. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]13.

MDMA enhances emotional empathy and prosocial behavior. Hysek CM, Schmid Y, Simmler LD, et al. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2014;9:1645–1652. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]14.

Differential effects of MDMA and methylphenidate on social cognition. Schmid Y, Hysek CM, Simmler LD, Crockett MJ, Quednow BB, Liechti ME. J Psychopharmacol. 2014;28:847–856. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]15.

Diminished medial prefrontal cortex activation during the recollection of stressful events is an acquired characteristic of PTSD. Dahlgren MK, Laifer LM, VanElzakker MB, et al. Psychol Med. 2018;48:1128–1138. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]16.

MDMA-assisted psychotherapy using low doses in a small sample of women with chronic posttraumatic stress disorder. Bouso JC, Doblin R, Farré M, Alcázar MA, Gómez-Jarabo G. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2008;40:225–236. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]17.

Durability of improvement in post-traumatic stress disorder symptoms and absence of harmful effects or drug dependency after 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine-assisted psychotherapy: a prospective long-term follow-up study. Mithoefer MC, Wagner MT, Mithoefer AT, et al. J Psychopharmacol. 2013;27:28–39. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]18.

3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA)-assisted psychotherapy for post-traumatic stress disorder in military veterans, firefighters, and police officers: a randomised, double-blind, dose-response, phase 2 clinical trial. Mithoefer MC, Mithoefer AT, Feduccia AA, et al. Lancet Psychiatry. 2018;5:486–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]19.

Breakthrough for trauma treatment: safety and efficacy of MDMA-assisted psychotherapy compared to paroxetine and sertraline. Feduccia AA, Jerome L, Yazar-Klosinski B, Emerson A, Mithoefer MC, Doblin R. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:650. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]20.

The ugly side of amphetamines: short- and long-term toxicity of 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA, 'Ecstasy'), methamphetamine and D-amphetamine. Steinkellner T, Freissmuth M, Sitte HH, Montgomery T. Biol Chem. 2011;392:103–115. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]21.

Distinct acute effects of LSD, MDMA, and D-amphetamine in healthy subjects. Holze F, Vizeli P, Müller F, et al. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2020;45:462–471. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]22.

Evaluating the abuse potential of psychedelic drugs as part of the safety pharmacology assessment for medical use in humans. Heal DJ, Gosden J, Smith SL. Neuropharmacology. 2018;142:89–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]23.

The experience elicited by hallucinogens presents the highest similarity to dreaming within a large database of psychoactive substance reports. Sanz C, Zamberlan F, Erowid E, Erowid F, Tagliazucchi E. Front Neurosci. 2018;12:7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]24.

Single versus repeated sessions of ketamine-assisted psychotherapy for people with heroin dependence. Krupitsky EM, Burakov AM, Dunaevsky IV, Romanova TN, Slavina TY, Grinenko AY. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2007;39:13–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]25.

A randomized trial of an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist in treatment-resistant major depression. Zarate CA Jr, Singh JB, Carlson PJ, et al. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:856–864. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]26.

Ketamine administration in depressive disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Fond G, Loundou A, Rabu C, et al. Psychopharmacology. 2014;231:3663–3676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]27.

The effect of a single dose of intravenous ketamine on suicidal ideation: a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis. Wilkinson ST, Ballard ED, Bloch MH, et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175:150–158. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]28.

Antidepressant efficacy of ketamine in treatment-resistant major depression: a two-site randomized controlled trial. Murrough JW, Iosifescu DV, Chang LC, et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2013;170:1134–1142. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]29.

Synaptic loss and the pathophysiology of PTSD: implications for ketamine as a prototype novel therapeutic. Krystal JH, Abdallah CG, Averill LA, et al. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2017;19:74. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]31.

Efficacy of intravenous ketamine for treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized clinical trial. Feder A, Parides MK, Murrough JW, et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71:681–688. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]32.

Efficacy, safety, and durability of repeated ketamine infusions for comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder and treatment-resistant depression. Albott CS, Lim KO, Forbes MK, et al. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79:0. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]33.

d-Serine is a potential biomarker for clinical response in treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder using (R,S)-ketamine infusion and TIMBER psychotherapy: a pilot study. Pradhan B, Mitrev L, Moaddell R, Wainer IW. Biochim Biophys Acta Proteins Proteom. 2018;1866:831–839. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]34.

Safety and efficacy of repeated-dose intravenous ketamine for treatment-resistant depression. aan het Rot M, Collins KA, Murrough JW, Perez AM, Reich DL, Charney DS, Mathew SJ. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:139–145. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]35.

Anxiety during ketamine infusions is associated with negative treatment responses in major depressive disorder. Aust S, Gärtner M, Basso L, et al. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2019;29:529–538. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]36.

Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: a randomized double-blind trial. Griffiths RR, Johnson MW, Carducci MA, et al. J Psychopharmacol. 2016;30:1181–1197. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]37.

Pilot study of the 5-HT2AR agonist psilocybin in the treatment of tobacco addiction. Johnson MW, Garcia-Romeu A, Cosimano MP, Griffiths RR. J Psychopharmacol. 2014;28:983–992. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]38.

Clinical interpretations of patient experience in a trial of psilocybin-assisted psychotherapy for alcohol use disorder. Bogenschutz MP, Podrebarac SK, Duane JH, et al. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:100. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]39.

Acute effects of LSD on amygdala activity during processing of fearful stimuli in healthy subjects. Mueller F, Lenz C, Dolder PC, et al. Transl Psychiatry. 2017;7:0. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]40.

Functional neuroimaging studies in posttraumatic stress disorder: review of current methods and findings. Francati V, Vermetten E, Bremner JD. Depress Anxiety. 2007;24:202–218. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]41.

Effect of psilocybin on empathy and moral decision-making. Pokorny T, Preller KH, Kometer M, Dziobek I, Vollenweider FX. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2017;20:747–757. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]42.

Psilocybin-induced spiritual experiences and insightfulness are associated with synchronization of neuronal oscillations. Kometer M, Pokorny T, Seifritz E, Volleinweider FX. Psychopharmacology. 2015;232:3663–3676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]43.

Patients’ accounts of increased “connectedness” and “acceptance” after psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression. Watts R, Day C, Krzanowski J, Nutt D, Carhart-Harris R. J Humanist Psychol. 2017;57:520–564. [Google Scholar]44.

Emotional breakthrough and psychedelics: validation of the emotional breakthrough inventory. Roseman L, Haijen E, Idialu-Ikato K, Kaelen M, Watts R, Carhart-Harris R. J Psychopharmacol. 2019;33:1076–1087. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]45.

The abuse potential of medical psilocybin according to the 8 factors of the Controlled Substances Act. Johnson MW, Griffiths RR, Hendricks PS, Henningfield JE. Neuropharmacology. 2018;142:143–166. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]46.

Integrating endocannabinoid signaling and cannabinoids into the biology and treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Hill MN, Campolongo P, Yehuda R, Patel S. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018;43:80–102. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]48.

Mitigation of post-traumatic stress symptoms by Cannabis resin: a review of the clinical and neurobiological evidence. Passie T, Emrich HM, Karst M, Brandt SD, Halpern JH. Drug Test Anal. 2012;4:649–659. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]49.

WHO proposes rescheduling cannabis to allow medical applications. Mayor S. BMJ. 2019;364:0. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]50.

A new ESI-LC/MS approach for comprehensive metabolic profiling of phytocannabinoids in Cannabis. Berman P, Futoran K, Lewitus GM, Mukha D, Benami M, Shlomi T, Meiri D. Sci Rep. 2018;8:14280. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]52.

Cannabinoid interventions for PTSD: where to next? Ney LJ, Matthews A, Bruno R, Felmingham KL. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2019;93:124–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]53.

Neurobiological interactions between stress and the endocannabinoid system. Morena M, Patel S, Bains JS, Hill MN. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2016;41:80–102. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]54.

Cannabinoid modulation of prefrontal-limbic activation during fear extinction learning and recall in humans. Rabinak CA, Angstadt M, Lyons M, Mori S, Milad MR, Liberzon I, Phan KL. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2014;113:125–134. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]55.

Cannabidiol disrupts the consolidation of specific and generalized fear memories via dorsal hippocampus CB1 and CB2 receptors. Stern CA, da Silva TR, Raymundi AM, et al. Neuropharmacology. 2017;125:220–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]56.

Fear extinction in traumatized civilians with posttraumatic stress disorder: relation to symptom severity. Norrholm SD, Jovanovic T, Olin IW, Sands LA, Karapanou I, Bradley B, Ressler KJ. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:556–563. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]57.

Preliminary, open-label, pilot study of add-on oral Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol in chronic post-traumatic stress disorder. Roitman P, Mechoulam R, Cooper-Kazaz R, Shalev A. Clin Drug Investig. 2014;34:587–591. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]58.

The efficacy of nabilone, a synthetic cannabinoid, in the treatment of PTSD-associated nightmares: A preliminary randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled cross-over design study. Jetly R, Heber A, Fraser G, Boisvert D. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2015;51:585–588. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]59.

The use of a synthetic cannabinoid in the management of treatment-resistant nightmares in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) Fraser GA. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2009;15:84–88. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]60.

Use of a synthetic cannabinoid in a correctional population for posttraumatic stress disorder-related insomnia and nightmares, chronic pain, harm reduction, and other indications: a retrospective evaluation. Cameron C, Watson D, Robinson J. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;34:559–564. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]61.

Cannabinoids for the treatment of mental disorders and symptoms of mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Black N, Stockings E, Campbell G, et al. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6:995–1010. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]62.

Practical considerations in medical cannabis administration and dosing. MacCallum CA, Russo EB. Eur J Intern Med. 2018;49:12–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]63.

Adverse health effects of marijuana use. Wolff V, Rouyer O, Geny B. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:878–879. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]64.

Cannabis and psychosis: are we any closer to understanding the relationship? Hamilton I, Monaghan M. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2019;21:48. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]65.

Prevalence and correlates of DSM-5 cannabis use disorder, 2012-2013: findings from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III. Hasin DS, Kerridge BT, Saha TD, et al. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:588–599. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]